Finns in the U.S.

- According to the US Census Bureau’ American Community Survey(Link to another website.), in 2018 there were 649,761 people reporting Finnish ancestry (with a margin of error +/- 17,113).

- In 2019, over 750 Finnish students studied in U.S. universities. Annually, about 200,000 Finns visit the United States.

- Did you know that a Finnish-American was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence? Mr. John Morton of Pennsylvania’s family heritage originates to Rautalampi, Finland.

Read more facts and figures about the Finns in the United States in our article series.

Interesting Facts and Figures About Finnish Migration at the Turn of the Century

How much do you know about the history of Finns in the U.S.? In this article, we take a look at some interesting facts about the Finns who arrived at the shores of North America at the turn of the century. While some Finns had traveled to the New Sweden colony during the country's time under Swedish rule, true widespread mass migration did not emerge until the 1800s.

An early-20th century Finnish passport on display at the Ellis Island Museum of Immigration.

The very first Finns arrived in Delaware Valley in North America in 1638 on two Swedish ships, the Kalmar Nyckel and Fågel Grip, when Finland was still a modest, impoverished country under Swedish rule. Finns, as subjects of the Swedish Crown, were included in Sweden's seventeenth-century effort to gain a foothold in the New World, and so approximately one thousand colonists in New Sweden are believed to have been Finns who had first settled in Sweden or who came directly from Finland. Martti Marttinen, born in Rautalampi, Finland, was one of these early settlers. He arrived in Pennsylvania in the 1650s, and his great-grandson John Morton(Link to another website.) eventually became one of the original signers of the Declaration of Independence.

It is believed that 19th-century Finnish migration to the U.S. began as a movement of sailors at the beginning of the 1800s, as Finnish sailors occasionally deserted the ships sailing in American coastal waters, choosing to remain in North America. However, proper mass migration began only after the American Civil War (1861 – 1865) and continued until the 1920s. Altogether approximately 389,000 Finns immigrated to North America during this time. The years between 1890 and 1914 were the most significant, as they saw over 200,000 Finns leaving for the U.S.

The majority of migrants were male tenant farmers and laborers from the countryside, many of them very young. The first large emigrant groups came from the vicinity of Kokkola and the Tornio River valley Northwest of Lapland around 1866. Oulu, Turku, Pori, and Vaasa also became major emigration hubs through the 1870s and the 1880s. By the 1890s, migration to the U.S. was almost countrywide, though a significant amount came from Ostrobothnia, a region in western Finland.

The Grand Duchy of Finland(Link to another website.) (Opens New Window), as the country was named until 1917.

There were many reasons for the rising interest in North America and migration in general at the end of the 19th century – some may have heard tales of the life in the U.S. from sailors, while others witnessed their relatives migrate to Sweden or Norway after leaving Finland behind for work and better living conditions. Moreover, North America had become an idealized land in the minds of the educated classes in both Finland and Europe, as its independence achieved in 1776 had stimulated new ideas of democratic freedom across the world. Even though the idea of the U.S. as an aspirational land of freedom slightly faltered with the Civil War (1861-65), many Finns and people across Europe were still curious to witness first-hand the great democracy on the other side of the ocean. Many people, laborers and intellectuals alike, were tempted by the continent's infinite possibilities. All across Europe, reasons for emigration were similar: economic hardships, changes in the societal atmosphere of one's home country, but above all, the hopes of a better life.

Now, we know what areas Finnish immigrants came from, but where did they settle within the U.S.? People from the same Finnish towns tended to immigrate to the same cities. For example, Oulu's share was large in the Pacific coast states, while most Finnish settlers in most North American "Finn Areas" like Ohio and Illinois came from the Vaasa province. Immigrants from the southern coastal area of Uusimaa were especially numerous in New York City. Finns spread far and wide: into the mines of the western mountains, the farms and lumber mills of the Great Lakes states, the factories of New York, and as time went on, into the auto plants of Detroit. In New York, Brooklyn and Harlem became lively centers of activity for the Finnish community.

The U.S. Immigration Station on Ellis Island, New York, the first stop for most of the more than 300,000 Finns who came to America from the late 19th century to the 1920s.

In particular, Michigan quickly became the undisputed heart of Finnish North America. It is even now the home to the first and only Finnish higher education institution in the U.S., Suomi College, now known as Finlandia University(Link to another website.). In the deep south of the 1920s, Finns from New York founded a settlement near Jesup, Georgia, by the name of McKinnon's cooperative farm. There was a favorable attitude towards the Finnish community in the area, and many people took part in the corner dances at "Finn Town." While the immigrant population was predominantly masculine, numerous women arrived on the shores of North America too. In particular, New York City attracted a significant number of Finnish women. Single women were often employed as domestic servants.

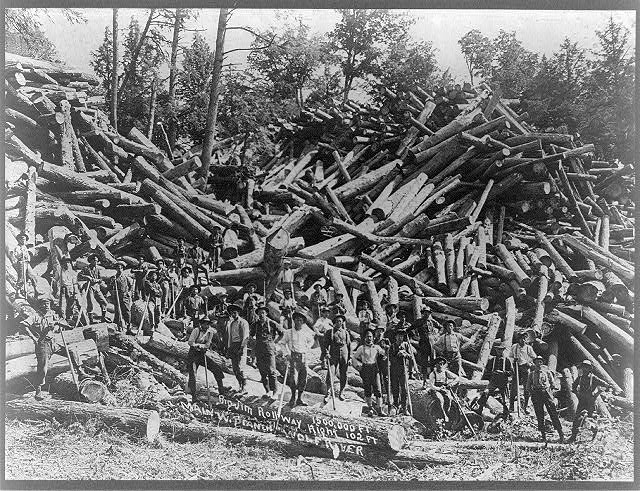

Photo: Library of Congress

Many Finns ended up working in logging.

For some, the adjustment to American life was slow and even painful. Even though Finnish immigrants were distinguished by their high literacy rate(Link to another website.) (Opens New Window), the Finnish language being radically different from other European languages made learning English a struggle for some, leading to many Finns being relegated to low-paying work that did not require language proficiency. Moreover, the decades of the highest Finnish immigration also saw the rise of increased public hostility towards immigrants. In fact, up to every fifth Finnish immigrant ended up returning home.

The 1920 federal census counted 150,000 persons born in Finland permanently living in the U.S., and 145,000 persons with one or two foreign-born Finnish parents, totaling around 300,000 Finnish-Americans, not counting those census enumerators did not find! During economic booms, the migration numbers increased significantly, and vice versa: emigration peaked between 1874 and 1893 and between 1894 and 1914.

As time went on, the immigrants' social and political backgrounds started to change – for example, the nascent Finnish labor movement was an increasing influence on the population. The First World War changed everything, abruptly ending the era of unfettered mass migration. While immigrants did keep arriving even after the war, the Immigration Act of 1924(Link to another website.) limited the number of immigrants allowed entry into the United States through a national origins quota.

While the number of Finnish immigrants pales compared to that of some of the other Nordic countries, emigration had a tremendous effect on Finland. In just a few decades, it lost roughly ten percent of its population to emigration.

Stay tuned for more on the history of Finns in the U.S.!

Article by: Sessi Trapnowski